The Huffington Post, September 8, 2010

The Huffington Post, September 8, 2010

Maan News Agency, September 10, 2010

Peace talks and the Israeli school year have started at about the same time. Which is more worthy of your attention?

The school year.

Peace talks are doomed to fail. Hamas, a key player, is being excluded. Just four months ago, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu proclaimed that “We will never divide Jerusalem.” And the settlement freeze–which saw construction on hundreds of new homes–is set to expire at the end of the month.

The list goes on.

The Israeli educational system is only slightly more promising.

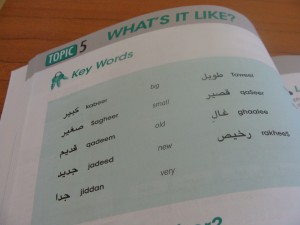

The start of the school year saw the introduction of a pilot program that will make Arabic classes mandatory for students in 170 schools in the north of Israel. Speaking to the Israeli news site Walla, Dr. Shlomo Alon, Head of Arabic and Islam Education in the Ministry of Education, remarked: “We live in a country that has two official languages… Studying Arabic will promote tolerance and convey a message of acceptance.”

Alon continued, “The state aspires to complete equality of citizenship. We will not deal with conflicts based on cultural identity.”

The rhetoric is great but the reality of the pilot program is a bit dimmer. Haaretz reports that it is a response, in part, to greater demand for Arabic matriculation exams. This means that the classes are intended primarily for Palestinian-Israeli students. It is Jewish-Israelis, not Palestinian-Israelis, who need to learn how to accept Arabic-speakers.

Further, the pilot program is being conducted in Israel’s North District–home to an Arab majority.

More encouraging are the Ministry of Education’s plans to make Arabic compulsory across the country. And it’s heartening that pilot program is the result of the tireless efforts and advocacy of The Abraham Fund, a local NGO that promotes “coexistence and equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab citizens” and was founded in the midst of the First Intifada.

But Israeli schools also hold some dark harbingers.

A recent poll conducted by Tel Aviv University professor Camil Fuchs found that 50 percent of Jewish-Israelis don’t want Arabs in their classes. And while nearly two-thirds of those surveyed acknowledge that Arab citizens don’t have equal rights, 59 percent are fine with that.

Racism takes other forms in Israeli schools. When school started last year, more than 100 Ethiopian students were barred from private ultra-Orthodox schools in Petach Tikva because of their ethnicity. More recently, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled against the segregation of Sephardi and Ashkenazi students in an ultra-Orthodox school– and Ashkenazi students skipped school in response.

At the same time that the Ministry of Education is launching its pilot program, it is rewriting its textbooks in a bid to “move the emphasis from citizenship and democracy” while “strengthening Zionism and national patriotism,” according to Hebrew University professor Dr. Ricki Tessler.

Even though 64 percent of students would likely agree with the statement “since its establishment, the State of Israel has engaged in a policy of discrimination against its Arab citizens,” the Ministry of Education will see this sentence, and others like it, struck from textbooks.

While Israel bears a greater responsibility than the Palestinians–it was the Jewish state that created the refugee problem in 1948, discriminates against its Arab citizens, and continues to occupy and illegally settle the West Bank–the PA has some educational work to do, too. Many Palestinians know little about the Holocaust, a horrendous chapter in Jewish history that continues to make an impact on the Israeli psyche and, arguably, influences the Israeli government’s policies for better or worse.

Two state, one state, or no state, our fates are bound together and our educational systems must reflect that. We must learn more than one another’s languages–we must know each other’s cultures, histories, and values. We must know each other’s humanity.

That the peace process has been stalled for years–and is likely to stall again–points to the urgency of a bottom-up solution. Only when the people demand peace will peace come.