+972 Magazine, October 20, 2015

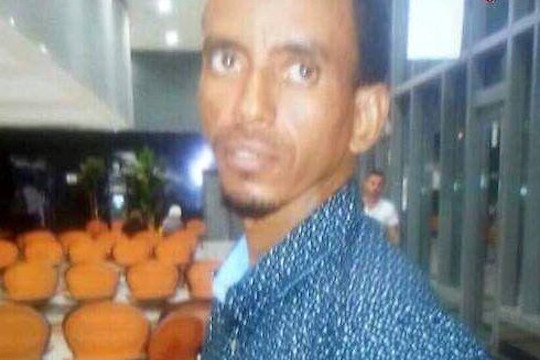

An Eritrean asylum seeker was mistaken for a Palestinian during ashooting attack at the Be’er Sheva bus station Sunday night. Habtom Zarhum, 29, was shot by a security guard who thought he was a terrorist and then – as the asylum seeker lay bleeding on the ground – civilians kicked him, cursed and spat on him. A bystander bashed his head in with a bench.

In a video that circulated on social media Sunday night, one man is seen holding a chair over Zarhum. It is not clear whether he was trying to harm the asylum seeker or protect him.

The video also shows a small number of policemen and civilians trying to stop the mob from further harming Zarhum. But their efforts were unsuccessful. At one point a man walks through the loose ring they’d formed around Zarhum, who was writhing in pain, and casually kicks his head like a soccer ball as he passes the already bloody and battered asylum seeker.

When medical personnel arrived, a crowd that was chanting “Death to Arabs” tried to prevent them from reaching Zarhum. The medics first treated the wounded Jewish Israelis. The asylum seeker was reportedly the last to receive help.

Zarhum later died of his injuries. Police on Tuesday said they were waiting to charge anybody in the death until an autopsy clarified whether the gunshot or the beatings caused his death.

Israeli media quickly labeled the incident a “lynch.” Yedioth Ahronoth, Israel’s top-selling daily newspaper, ran a photograph of Zarhum lying in his own blood and trying to protect his head, on the front page of Monday’s paper with the caption “A terrible mistake.” The article inside the paper was titled: “Just because of his skin color.”

Members of Israel’s African asylum seeker community expressed sadness and shock. Asylum seekers who are currently imprisoned in the Holot detention facility — where they are held for no specific crime and without trial for 12 months — held a vigil yesterday in Zarhum’s memory.

Dawit Demoz is a 29-year-old asylum seeker from Eritrea who has been in Israel since 2009. He criticized the security guard who shot Zarhum for using racial profiling, “You don’t just shoot [because of] the way [someone] looks. [Zarhum] didn’t do anything, he was trying to escape like everyone else… he was just trying to run away from the terrorist.”

Activists, asylum seekers and refugee advocates Israel were quick to point to the incitement directed toward African asylum seekers — by politicians, state institutions and the media — as necessary context for the killing in Be’er Sheva. “You leave a horrible situation [in Eritrea or Sudan] and when you come here and call yourself an asylum seeker, [the government and media] call you an infiltrator,” Demoz explained, referring to the term the Israeli government and media use to refer to African asylum seekers, a term rights groups have long decried as derogatory and inflammatory.

In death, however, Israeli media has taken to calling Zarhum an asylum seeker, “the Eritreat,” and in some cases, even a refugee. Police, strangely, began referring to him as a “foreign subject.”

Rotem Ilan, head of the migration department at the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, echoed the same sentiment. “You can see the difference between how the media talks about asylum seekers every day and how they talk about them when they die. Suddenly, they don’t use the word infiltrator,” she said, “suddenly he’s a human being.”

The lesson Ilan hopes that Israel will take from this incident, she continued, is “to treat people as human beings while they’re still alive.”

Some 45,000 African asylum seekers, most of whom are from Eritrea and Sudan, are currently in Israel. Authorities systematically reject or ignore almost requests for refugee status by African applicants. Israel has granted refugee status to only four Eritreans and no Sudanese nationals. In the European Union, by comparison, Eritrean asylum seekers’ applications for refugee status receive a positive answer 84 percent of the time.

At the height of their migration to Israel, there were 60,000 asylum seekers but numbers have waned as a result of an official policy to “make their lives miserable” and encourage those who are here to leave. Numerous Israeli officials have called African asylum seekers a demographic threat.

While Israel cannot deport Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers directly back to their countries of origin — because it would blatantly violate the principle of non-refoulement — most of the asylum seekers who live here do not receive work visas. With no legal way to survive, they work low-paying black market jobs where they face exploitation.

Israel has also tweaked its 1954 Prevention of Infiltration law, which was initially created to stop Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes, broadening the legislation to imprison African asylum seekers. The Israeli High Court of Justice rejected the legislation that authorized indefinite detention twice as unconstitutional, and upheld a third version while limiting the administrative detention of asylum seekers to one year.

Some activists, like Ilan, are pointing a finger at politicians for fomenting the conditions of xenophobia and vigilante violence that led to Zarhum’s death.

In the wake of stabbing attacks carried about Palestinians from East Jerusalem and the West Bank, politicians and state officials — including Knesset Member Yair Lapid, Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat, and the Jerusalem District Police Commander Moshe Edri — have encouraged Jewish Israelis to arm themselves and to “shoot to kill,” as Lapid put it. Last week, human rights groups issued a public letter expressing their concern about such statements.

ACRI, where Ilan works, sent an additional letter to the country’s attorney general warning of the consequences of such dangerous rhetoric.

“In such a tense time the leader’s job is to calm things down not to add fuel to the fire,” Ilan reflected. “In our letter we said that the end result of this current atmosphere and [politicians’] careless [remarks] is that innocent people will be hurt. This is what we saw yesterday.”

Unfortunately, this is far from the first time asylum seekers have experienced violence at the hands of Jewish Israelis. For years, the community has dealt with near-constant, low-level violenceaccentuated by more serious attacks. Things boiled over in 2012, when a small race riot broke out in south Tel Aviv after Knesset Member Miri Regev, who is part of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party, called African asylum seekers a “cancer in our body.”

When asked whether or not he feels safe in light of yesterday’s events, Demoz sighed and answered, “I don’t know what I’m feeling really. It’s hard for me to answer this question.”

*While the Israeli media has identified Zarhum as Haftom Zarhum, he has been identified by the African Refugee Development Center as Habtom Zerhom.