The National, August 28, 2012

South Africa has decided that anything produced in the West Bank must be labelled as coming from the Occupied Palestinian Territories, rather than Israel, as the labels now read. The ruling suggests that the global movement known as “Boycott Divestment and Sanctions” is picking up speed.

But Israel is also stepping up its process of forced relocations from the land, increasing pressure on Arabs on both sides of the Green Line. The forced transfers most often associated with the 1948 war did not end with the armistice agreements. They continue today, through overt plans to “relocate” Bedouin citizens of Israel using bureaucratic manoeuvring and the manipulation of the law that pushes West Bank Palestinians off their ancestral lands.

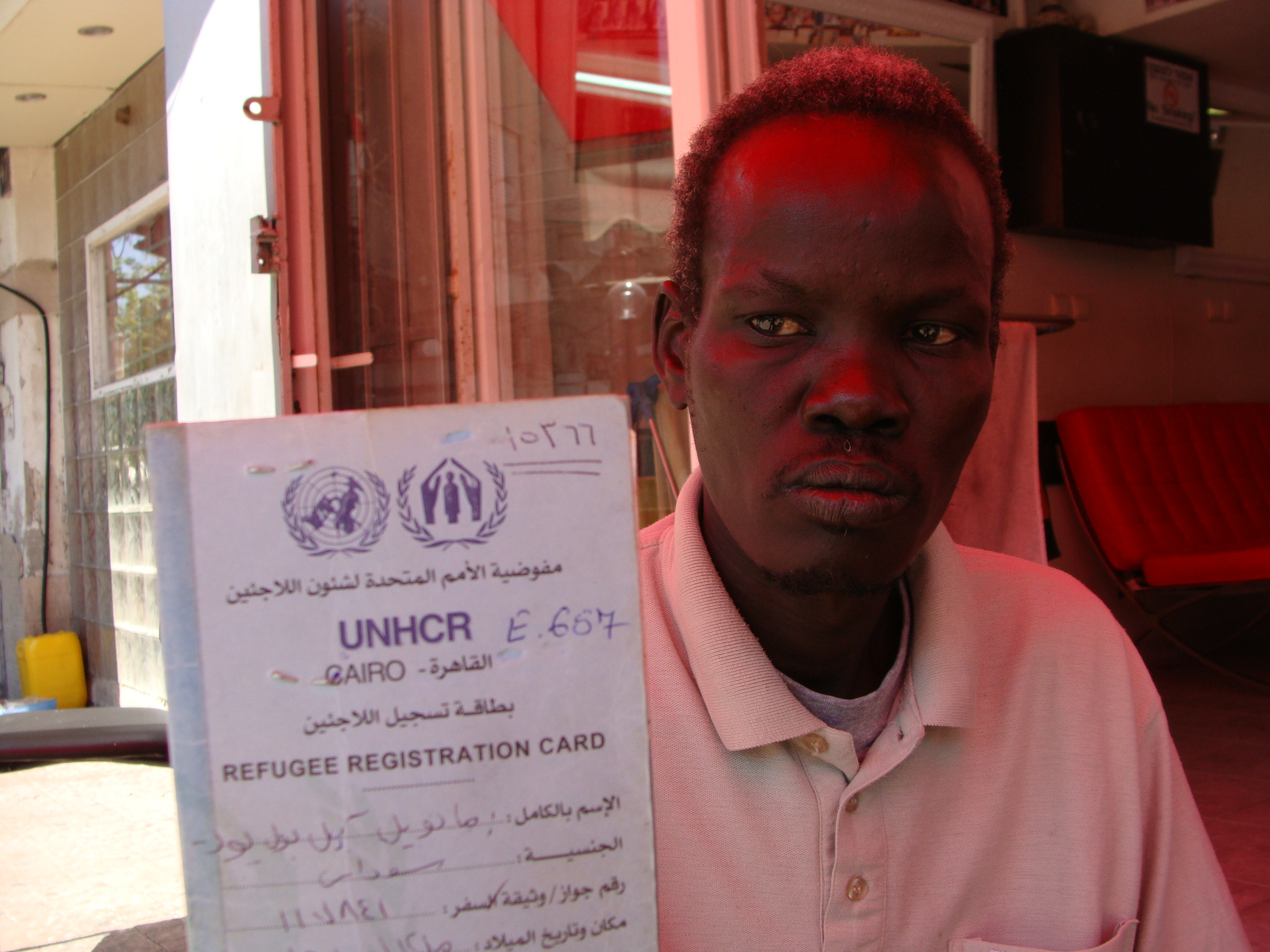

The United Nations reports that in the first six months of this year, Israeli demolitions in “Area C” – which makes up 61 per cent of the West Bank – led to the “forced displacement” of 615 Palestinians and Bedouins, more than half of them children. If demolitions continue at this rate, displacements will exceed those of 2011, in which 1,095 people were made homeless by Israel.

In Area C, dozens of Palestinian and Bedouin villages are threatened with demolition, and over 27,000 men, women and children face forced transfer. Most of these people are refugees.

The Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem says the Israeli civil administration will begin by relocating those closest to Jerusalem and will work its way out, finishing with those in the Jordan Valley. The 2,300 Bedouin men, women and children who live alongside the Israeli settlement of Maale Adumim, which many Israelis consider a suburb of Jerusalem and which the state intends to expand, are in the most immediate danger of expulsion. Among other options, the Israeli government is examining the possibility of moving them to the edge of a rubbish dump.

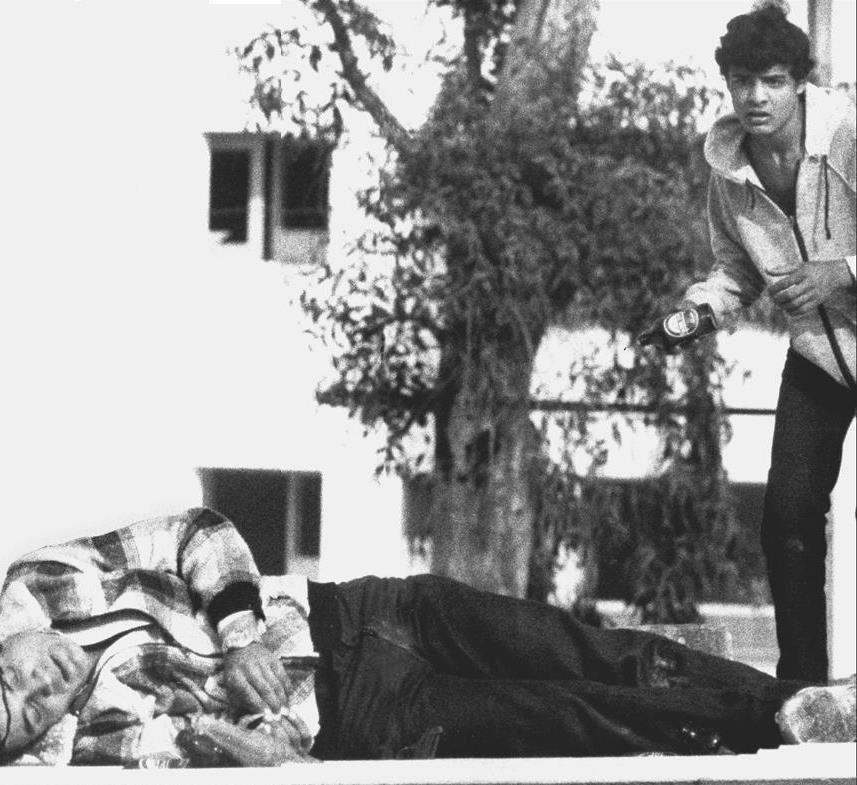

In other cases, Israel is not offering Palestinian and Bedouin residents an alternative location – the state is simply destroying their homes, leaving families to fend for themselves.

That’s the story in Susya, a small village in the south Hebron Hills. Israel claims the structures there are illegal because they were put up without building permits. But for the most part, the civil administration won’t issue building permits to non-Jews in Area C.

And if the state has its way, another 1,500 Palestinians will be displaced from the area that Israel has just recently named Fire Zone 918. Ten Israeli outposts have been built in such fire zones; their residents do not face expulsion.

Israel also has plans for Palestinian citizens of Israel who live inside the Green Line. Under Israel’s Prawer Plan, between 30,000 and 40,000 Bedouin face forced transfer from their villages in the Negev to townships that are little more than ghettos. Before the Prawer Plan was approved by the Israeli cabinet last September, the state had already demolished the unrecognised Bedouin village of Al Araqib dozens of times. At the time of writing, Al Araqib has been destroyed 41 times in two years.

But demolitions and forced transfers are not new to the Negev. In his book Palestinians in Israel: Segregation, Discrimination, and Democracy, Ben White notes that more than 2,000 Palestinians “were ‘transferred’ to Gaza in 1950” from the Negev and villages near the borders. Between 1949 and 1953 Israel expelled some 17,000 Bedouin from the Negev, White adds. In the decades that followed, Israel demolished thousands of homes in unrecognised Bedouin villages.

Elderly residents of the occupied Syrian Golan Heights recall Israeli soldiers forcing Arabs from their homes during and after the 1967 war. Decades later, witnesses described how Israeli soldiers “forced [Syrians] from their homes … fired their guns into the air and told them to leave”. They also described how those who took refuge from the fighting in neighbouring villages were prevented from returning to their houses. Approximately 120,000 Arabs were expelled or fled the area, which Israel unilaterally annexed in 1981.

The Israeli government also uses other, less direct methods to encourage non-Jewish Arabs to relocate. In the West Bank and Gaza, Israel has purged more than 150,000 Palestinians from the population registry – making it impossible for them to return or to get identification cards.

B’Tselem estimates that nearly 650,000 Palestinians who live in the occupied territories have an immediate family member who is unregistered, and thus paperless. Israel has ignored over 100,000 requests for family reunification.

In the West Bank, Israel restricts Palestinian and Bedouin access to water, crippling agriculture, the traditional livelihood of many residents. And of course there is the separation wall and the system of checkpoints and permits, making it difficult for many – and impossible for some – to reach schools, work, health care, friends and families. The resulting economic and psychological pressures have led some to emigrate.

Al Araqib and the Prawer Plan – and the rise in demolitions and displacements – made international headlines, which may give the impression that forced transfers are a new Israeli strategy, or at least one that has been resurrected from the 1948 war. But this is not the case. The current and upcoming relocations must be understood as part of an ethnic cleansing process, taking both overt and bureaucratic forms, that began 64 years ago and that will end only when the international community no longer allows it to continue.