Le Monde Diplomatique, July 2, 2012

It was a winter morning in 1982. Shimon Yehoshua, 21, had finished three years’ mandatory military service a week before. He’d arrived at his home—two rooms shared with his parents and nine brothers and sisters—in time to catch the last flames of Hanukkah.

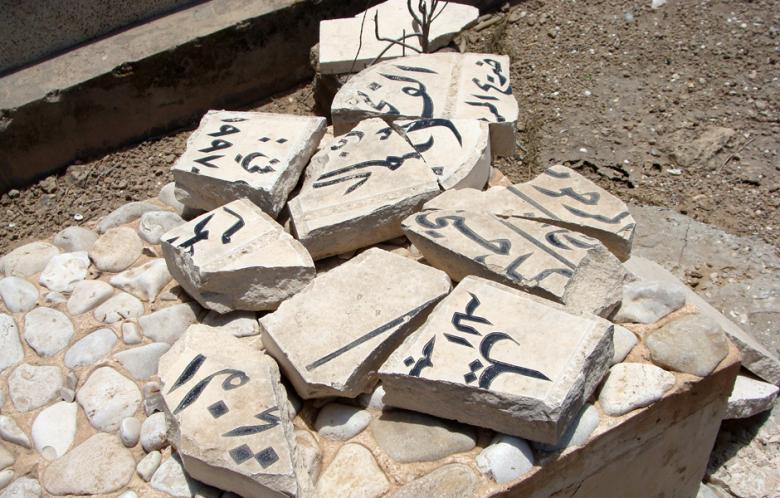

Shimon lived in the Kfar Shalem neighborhood in the poor south of Tel Aviv. Before the 1948 war, Kfar Shalem was a Palestinian village, Salame. After the fighting was over the new state of Israel confiscated it and put mizrachim (Jews from Arab countries) in the homes, effectively turning them into public housing. By the 1970s, however, it was kicking those same families out to make way for more profitable projects like high rises.

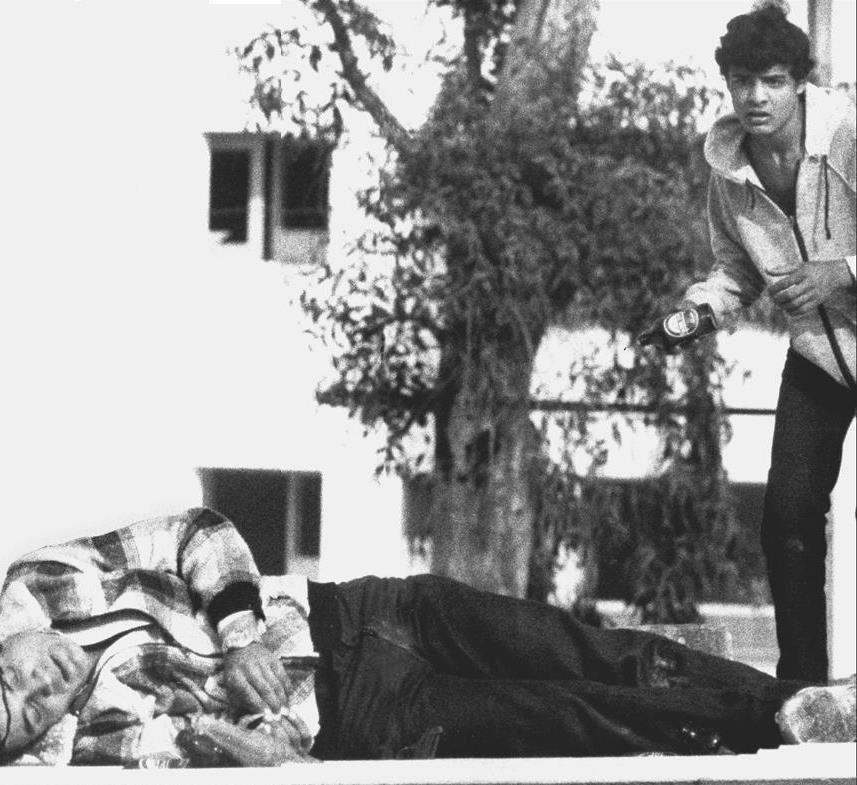

When the police arrived to evict the Yehoshua family in December 1981, Shimon and a younger brother took to the roof in protest. Shimon was a handsome young man with dark, wavy hair, high cheekbones and a square chin. He wore jeans and a plaid jacket too thin to protect him from the cold. He was unarmed, save for some empty beer bottles.

Word of the standoff quickly spread through the neighborhood. Locals rushed to the scene. Zacharia Terem, now 81, was among them. In Hebrew thick with a Yemeni accent, Terem recounted the incident: “The police came. Shimon got on the roof. And they killed him.” Terem raised his arm, his hand jerked as though he was firing a gun. “The officer was close—five, six meters away. He shot him twice. Once in the head and once in the shoulder. If you want to disable someone, you shoot them in leg. You don’t kill them.”

Thirty years on, Terem is still rattled by the incident. He paused, shook his head and rested his hand on his heart. He told me that in 1982 he was a technician at the phone company; he was also a founding member of the neighborhood committee formed to address the community’s needs. The state neglected mizrachi in south Tel Aviv and the area was plagued with crime, violence and drugs.

He recalled how Shimon lay still on the roof, his younger brother standing behind his body, gripping an empty bottle, as Terem confronted the police officer. “‘You’re a real hero!’“ he shouted, wagging his finger in the air. “‘A hero!’” The man who killed Shimon was never prosecuted.

***

Terem and his wife have lived in the same home in Kfar Shalem since they came to Israel from Yemen in 1949. They raised six kids in this house, which had no electricity and no running water when they arrived. Terem took to working the land: jasmine, mango, orange, palm and gat trees blanket the dunamand a half he calls his own.

Today, several generations of his family live in the small homes scattered along the edges of the lot. As Terem and I chatted, a grandson dropped by. He kissed the mezuzah on the doorpost as he entered and welcomed me in Arabic,ahlan wa sahlan. A great granddaughter—a tiny, smiling girl with curly hair—scooted by on a tricycle. It’s quiet here. The skyline is low and the wind sweeps in from the sea. Kfar Shalem is far enough out of the city to feel like an escape, close enough to feel like part of Tel Aviv. There are wide, green spaces. Property taxes are relatively low.

It’s prime real estate. And the state now wants to expel the Terem family—without compensation—so it can turn the property over to developers. Yudit Ilany is a legal coordinator at Darna, the Popular Committee for Housing Rights in Jaffa. According to Ilany, 800-900 families face eviction from public housing throughout Israel. Many live in Kfar Shalem and Jaffa (historically Arab, now a part of the Tel Aviv municipality); most are mizrachi or Palestinian—two of society’s weakest socioeconomic groups.

While a few do have the means to buy their homes from the government, Ilany says, the state refuses to sell to them. Darna is fighting two such cases in court. Both houses are in Jaffa, which is undergoing gentrification; the state intends to auction the properties to the highest bidder.

With the municipality’s blessing, developers have plans for other south Tel Aviv neighborhoods, Shapira and Neve Shaanan. But this is nothing new. Savvy investors first swooped in to the area during the British mandate.

***

Architect and historian Sharon Rotbard explains that the Shapira neighborhood was founded by a speculator of the same name. In 1881, at the age of 14, Shapira left his native Lithuania for Detroit, Michigan. There, he made a small fortune in real estate. In his 40s, he brought this money to Palestine and started buying and developing land.

It wasn’t just Shapira. According to Rotbard, what is now called south Tel Aviv was the “wild south from the real estate point of view. It was absolutely capitalist.” Shapira, Neve Shaanan and the surrounding areas were the “Hebrew neighborhoods of Jaffa,” Rotbard says. “Yes, they were Jews… but they were also part of Jaffa… [and they] also had connections with the [Palestinian] locals.”

While some of the early residents were Zionists who had come for ideological reasons, more had fled the First World War and the Russian Revolution. Others were economic refugees. Here, they put a foot on the bottom rung of the socioeconomic ladder. When they wrenched themselves up, they headed north to Tel Aviv. “Since the 1920s, [these neighborhoods] have had waves of immigration,” Rotbard says. The first was Eastern European; the next brought Jews from Salonika [Greece], Bulgaria, and Turkey. The 1930s saw an influx ofBukhari from Central Asia.

But these groups moved on and today’s veteran residents of Shapira and Neve Shaanan are mostly Bukhari and Russians who arrived in the 1990s. In recent years, Jewish settlers from the West Bank have migrated to south Tel Aviv and Jaffa. The phenomenon is an attempt to push Israeli society further to the right.

“There is a lot of power here that wants [the neighborhood] to be just for the Jews,” Rotbard said: “When I [moved to Shapira] in 2000, there were many [undocumented] Palestinian workers here from the West Bank [and Gaza]. They were here just like the Sudanese and Eritrean live here today.”

***

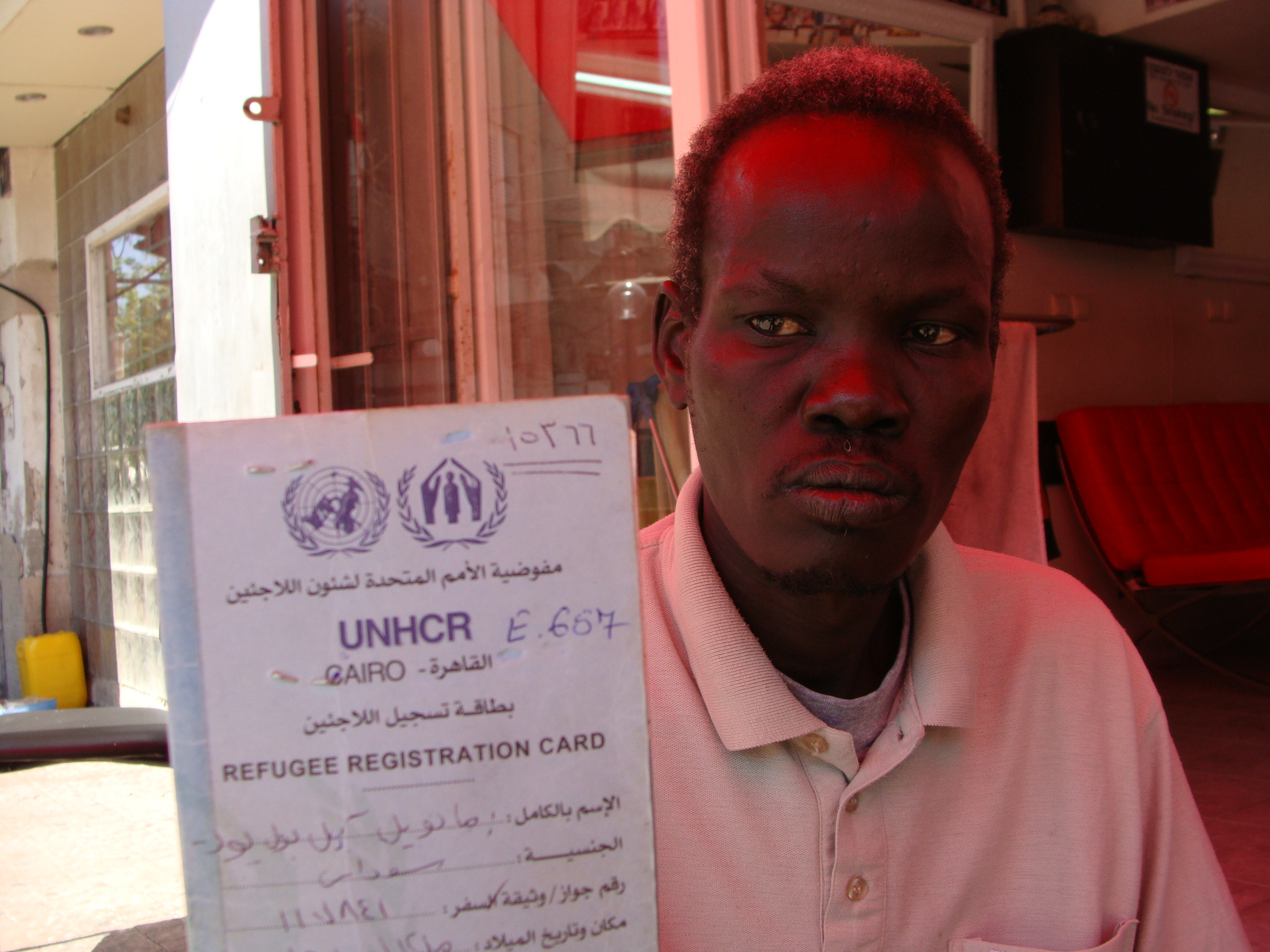

Since 2005, Shapira, Neve Shanan and HaTikva have become home to a large population of African refugees. They enter Israel via the porous southern border with Egypt. After they are arrested and held in prison, Israeli authorities dump the refugees in south Tel Aviv’s poor neighborhoods. Today, tens of thousands live in the area between the Central Bus Station and Kfar Shalem. Countrywide, they number 60,000.

For the most part, Israel does not process their requests for asylum: as Kfar Shalem residents are quick to point out, recognizing African refugees could open the door to Palestinian refugees. And while the state issues the asylum seekers visas, it calls them “illegal infiltrators” and does not allow them to work. So they scrape by on odd jobs and crowd into inexpensive apartments, sleeping as many as 20 to one room. Some refugees live in south Tel Aviv’s parks.

Rather than addressing the issue, state officials began campaigning against the asylum seekers. In October 2009, Interior Minister Eli Yishai said Africans bring “a profusion of diseases” to the country. In July 2010, 25 south Tel Aviv rabbis issued a letter forbidding Jews from renting to “infiltrators” and undocumented migrant workers. That same month, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called Africans a “concrete threat to the Jewish and democratic character of the country.”

Soon thereafter, south Tel Aviv residents—mizrachim, Russians and settlers alike—started protesting against the refugees, calling on the state to deport them. Knesset members have joined these demonstrations, suddenly remembering the long-neglected locals.

In May, one such protest turned into a race riot after Member of Knesset Miri Regev, from Netanyahu’s Likud party, likened asylum seekers to “cancer in our body.” Some Jewish Israelis broke the windows of African-owned businesses, looted, and attacked refugees on the street. Incidents of violence are ongoing.

***

Although the protests are xenophobic and dangerous, the demonstrators accurately point out that they are a weak group that can’t handle the influx of another needy population. They are also correct when they say that the government doesn’t do anything to help.

Some critics say that the state is going beyond neglect. According to Ilany and City Councilman Aharon Maduel, the government is using this latest wave of immigrants to push the older ones out, intentionally fanning the flames in south Tel Aviv to serve developers’ interests—the same interests that pushed Yehoshua onto the roof.

Maduel is a member of the opposition party, Ir LeKulanu (A city for all of us). The son of Yemeni immigrants, he was born and raised in Kfar Shalem. Today, he lives there under the threat of eviction. Maduel says that it’s no accident that the refugees ended up in Shapira, Neve Shanan, and other south Tel Aviv neighborhoods. There is very little public housing in these neighborhoods, so the state cannot evict residents outright. Instead, the government must find creative ways to deliver the land to developers.

“How do you turn [south Tel Aviv] into an area for the rich?” Maduel says. “First of all, you weaken the area… forcing the people who have enough money to run… Only the weakest stay; the value of their houses goes down drastically; and the [investors] come and purchase, purchase, purchase….”

Ilany points out that in the same period that the refugees arrived, the government issued over 75,000 new work visas to non-Jewish migrant laborers. Though their numbers are greater than the refugees, politicians don’t call them a threat to the character of the state. Critics also say that the government points a finger at the refugees to divert attention from its treatment of the neighborhoods. It’s not just evictions. South Tel Aviv’s schools are weak and services are few. In Kiryat Shalom, for example, the municipality refuses locals’ requests for a library. And while wealthy north Tel Aviv has numerous sports and swimming facilities, Kfar Shalem’s 45,000 residents have just one small gym and a pool that is only open in the summer.

Maduel says it all boils down to discrimination against mizrachim. If the population was a different color, he says, they wouldn’t be struggling to hang on to their homes. And, maybe, Shimon Yehoshua wouldn’t have died defending his.